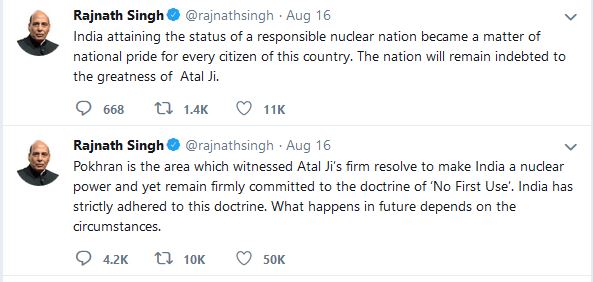

When India’s Defense Minister Rajnath Singh recently hinted that India could opt for “first use” nuclear doctrine depending upon circumstances in future, there was hardly any strong reaction against it either within India or abroad. The reason is not hard to discover. Many champions of nuclear non-proliferation and even other nuclear weapon powers are not in a position to moralize and advise India against it.

The world is undergoing rapid changes, and the global power structure is in for a major transformation. The single superpower, the United States, recently walked away from the 1987 Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) agreement that happened to be the sole success story of efforts towards nuclear disarmament. Rest of the agreements, such as SALT, START, etc. were nuclear arms control agreements. The US self-admittedly is seeking to defend itself by expanding and strengthening its nuclear/missile arsenal against suspected new nuclear missiles under construction in Russia.

Russian leaders for long have had abandoned the No-First-Use doctrine on the basis of the contention that the United States has tremendous conventional superiority and Moscow cannot wait for a first strike before considering the use of nuclear weapons. Unlike the understanding reached between Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev with the US and its NATO partners, NATO was not only given a new lease of life with redefined purpose but also was expanded close to the borders of Russia after the post-Cold War era. Deepening mistrust between Washington and Moscow has created a new cold war type situation in Eurasia.

The Trump Administration’s views on NATO have compelled the European Union to search for a new kind of defense arrangement. With BREXIT, the EU would have only one nuclear weapon power as its member. China, on the other hand, has been an aspiring superpower challenging the current international order headed by the United States and has left no stone unturned to maintain a robust, sophisticated and powerful nuclear and missile arsenal.

Pakistan is a terror-sponsoring country that seeks to develop strong nuclear deterrence to back up its policy of waging low-intensity conflicts with neighbors. Despite a severe economic crisis, Islamabad has consistently been expanding its nuclear and missile capability. It is significant to underline that it unleashed a dangerous misadventure in Kargil months after going nuclear. At every drop of a hat, Pakistani leaders brandish their country’s nuclear weapon capability.

More importantly, political debates on the need for keeping a nuclear weapon option open are currently going on in two countries in the Indo-Pacific that have been diehard champions of nuclear non-proliferation. Those two countries are Japan and Australia. Neither Japan nor Australia actually aspires for great power status. The current thinking in some sectors of the policy analysis community in those countries is influenced by adverse strategic developments in the Indo-Pacific region. The hesitation by the Trump Administration to extend credible nuclear umbrella to its time-tested allies, the Chinese expansionism in South China Sea, North Korea’s persistent missile tests and belligerent behavior, brewing Sino-US Cold Confrontations and the growing rift between Japan and South Korea, albeit on trade issues, have created a scenario that encourages Australia to experiment with a nuclear option and Japan to stay away from signing and ratifying the UN nuclear ban treaty.

In the backdrop of all these developments, it is only logical, relevant, and desirable that the Indian Defense Minister signaled a possible change in the country’s nuclear doctrine. The vow not to be the first country to use nuclear weapons when there is an existential threat is both illogical and immoral. However, the promise of not using nuclear weapons against a non-nuclear weapon power is quite acceptable, and the capacity to possess a second-strike capability is equally necessary and adorable.

But all the theories and doctrines of war-fighting, nuclear use, non-use of chemical and biological weapons become academic when the war begins. Ethics, morality, responsible behavior, humane approach are important while imparting training to military forces, but when aggression takes place, the military is expected to defend the country.

It is true that nuclear weapons have to be treated as political weapons. They are weapons of last resort, and their uses make it difficult to protect nature’s creation and humanity. It would have been better if nuclear weapons had not been invented. But the reality is that they are there. The fact remains that efforts to establish a nuclear-free world have so far failed.

It is true that nuclear weapons have to be treated as political weapons. They are weapons of last resort, and their uses make it difficult to protect nature’s creation and humanity. It would have been better if nuclear weapons had not been invented. But the reality is that they are there. The fact remains that efforts to establish a nuclear-free world have so far failed.

As far as others have nuclear weapons or capability to develop such weapons, India’s expensive nuclear arsenal should not be bound by a doctrine that could encourage known or unknown enemies to pose an existential threat to India. This is much more necessary when unfriendly countries have conventional superiority or nuclear capability.

India is a peaceful country that is known to all. That India has never indulged in imperialistic expansion abroad is a fact of history. That contemporary India has been a victim of aggression is also well known. That India has been a successful democracy, responsible actor in international affairs and a champion of regional peace and global stability is beyond doubt. Abandoning the no-first-use doctrine may alert the enemies but surely will not threaten others.

![]()