The SCS Conundrum

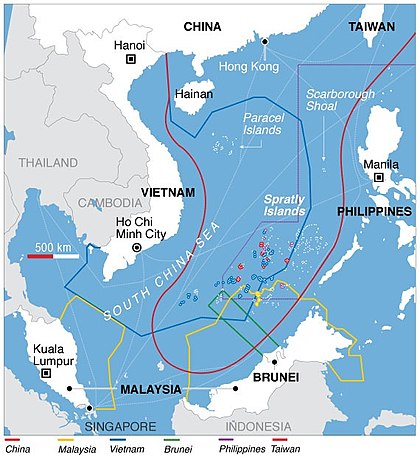

The South China Sea (SCS) comprises of over 250 small islands, atolls, cays, shoals, reefs, and sandbars. These can be mapped along with seven major archipelagos, namely, Spratly, Paracel, Natuna, the Anambas, the Macclesfield Bank and Scarborough Shoal. This region shares borders with (clockwise from north) China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, Singapore, and Vietnam.

Historically, China, along with most of ASEAN countries are littoral states interested in retaining or acquiring their respective rights to fishing stocks, sea exploration and potential exploitation of crude oil and natural gas in the seabed in various parts of the SCS and the strategic control of important shipping lanes. But, China has started claiming sovereignty over the entire SCS, overlapping with the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) claims of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam.

China has taken control over the Paracel Islands (from 1974), Macclesfield, Pratas, and Scarborough Shoal (from 2012) by force. Vietnam controls the twenty-nine of features in the Spratlys Islands, wherein China has eight, while the Philippines has control of eight features, Malaysia controls five, Brunei controls two, and one by Taiwan.

Disputes and contests in the SCS had aggravated since 2013 when China started its island-building activities in the region. In January 2013, the Philippines formally initiated arbitration proceedings against China’s claim on the territories within the “nine-dash line” that includes the Spratly Islands, which it said is “unlawful” under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). An arbitration tribunal was constituted under Annex VII of UNCLOS, and it was decided in July 2013 that the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) would function as the registry and provide administrative duties in the proceedings.

On 12 July 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) Tribunal nullified Chinese claims on practically the whole of SCS and its so-called historical rights and nine-dash line. PCA Tribunal has pointed out that Beijing had no entitlement to an exclusive zone (EEZ) within 200 nautical miles of the Spratly Islands. The judgment also indicted Beijing for destroying marine ecology and the environment by establishing artificial islands and militarizing them for bolstering its claims. The PCA ruling is undoubtedly a victory for a 21st-century rules-based order over China’s 19th-century plans for its own sphere of influence. China has rejected and ignored it.

Chinese ambitious plans can be understood from the fact that it has built three new airports in 2016, namely, Yongshu Airport, Zhubi Airport, and Meiji Airport on reclaimed lands in SCS.

Further, China has taken the approach of imposing unilateral decisions as solutions to these conflicts. These unilateral solutions can neither deal with regional security challenges nor fulfill the littoral states’ demand for maritime resource sharing. The economic and military capabilities of China are ahead of any Asian nation. This superior position helps China undertake assertive posture and insist that any resolution should be through bilateral negotiations with other claimants. All littoral states of SCS are at a disadvantage due to the belligerent attitude of China.

China unilaterally declared that the “nine-dash line”, a vast, U-shaped expanse, marks China’s territorial claims in the SCS, including large swathes of Vietnam’s continental shelf where it has awarded oil concessions to Russia and India. India has requested the renewal of the contract with regard to exploration rights in Block 128, which is located in the Vietnamese Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The contract for exploration had expired in June 2019. This exploration initiative to renew the contract is meant as much to secure energy interests as it is to give a signal to China that India would not succumb to Chinese bullying tactics and is a legitimate stakeholder in SCS through a partner country. However, China has threatened the joint exploration initiatives of Russia, India, and Vietnam near Vanguard Bank. India and Russia have recently opened Maritime Route between Chennai and Vladivostok. The new route passes through the SCS. Therefore, India and Russia’s increasing cooperation with Vietnam will contribute to improving the efficiency and safety of this route.

SCS: a part of Indo-Pacific Maritime Challenges

SCS is situated between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. In fact, SCS is a small sea in the Pacific Ocean. Hence, it is a part of the Indo-Pacific maritime landscape for India. The region is spread over three distinguished straits with water bodies of vast geo-economic, geo-strategic, and geopolitical importance. First is the Taiwan Strait, which separates the island of Taiwan from Mainland China. This route is important from the point of view of uninterrupted supplies for Indo-Russian trade flow through this strait. Second is the Karimata Strait separating the Indonesian Islands of Sumatra and Borneo (Kalimanta). These routes provide and support the extended neighborhood policy for Indo-ASEAN trade and maritime navigation. The third is the Malacca Straits, the main shipping channel between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, and arguably the most important shipping lane in the world. The area around the Strait is also one of the busiest shipping routes in the world.

More than half of the world’s annual merchant fleet uses the route, and a third of all maritime traffic worldwide passes through these waters. An estimated over US$4.5 trillion worth of global trade passes through the SCS annually, which accounts for a third of the global maritime trade. More than half of all oil transported by sea crosses through this region. This traffic is three times greater than that passing through the Suez Canal and fifteen times more than the Panama Canal. The waters in this region contain lucrative fisheries, which are crucial for the food security of millions in Southeast Asia. Huge oil and gas reserves are believed to lie beneath its seabed. Therefore, this critically important international maritime route and surrounding water bodies cannot be under the strict sovereign control of a single country, especially one which has an expansionist mindset.

Over 55 percent of India’s trade passes through the SCS, making peace and stability in the region of great significance. India undertakes various activities, including cooperation in the oil and gas sector, with littoral states of the SCS too. India has high stakes in the uninterrupted flow of commercial shipping in the SCS, and also in maintaining the free movement of its Navy in these waters. For India, the SCS region holds importance in terms of its trade with the Asia-Pacific region and the conceptualization of a free, open, and inclusive Indo-Pacific. As such, there is some apprehension that complete control over SCS by Chinese maritime forces would have a spillover effect on the Strait of Malacca chokepoint, which is a strategic point of entry into India’s backyard in the Indian Ocean.

Most commentators on this subject believe that China’s expansive claims on the SCS come at the expense of the legitimate claim of most ASEAN countries. Its land-grabbing techniques by stealth, artificial island-building, and subsequent militarization, etc. have reached a dangerous proportion, turning SCS into a flashpoint that can go out of control in the future. Further, it will impact the stability, security, peace, and, ultimately, freedom of navigation throughout Indo-Pacific trade routes.

Act East Policy and Way Ahead

India has changed its strategic goals under Modi 1.0 regime from Look East Policy (LEP) to Act East Policy (AEP). India’s strategic ties with countries in the region, especially with Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Vietnam, and the Philippines, have become stronger under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s AEP. India increased the activities with SCS littoral states through naval exercises and visits, strategic partnerships, oil exploration, and through diplomatic discussions at multilateral forums.

Under the AEP, India has enhanced focus on maritime strategy in the Indo-Pacific region. This has come out most significantly in working closely with ASEAN countries. India’s AEP has also allowed it to think broadly in terms of maritime trade, blue economy, naval requirements, and capabilities, etc. India has a long coastline with a blue water navy, comprising 90 percent of international trade by volume and 77 percent by value. This maritime route is pivotal in the Indo-Pacific trade. For India, ASEAN is not just a getaway into and out of the Indian Ocean but is one of the most dynamic groupings – economically and politically.

Modi 2.0 regime has coincided with many of geopolitical churnings globally and in Asia pacific particularly. This includes the bi-directional impact of the Indo-pacific strategy with its “free and open” conception of the region primarily led by the US and India, the global impact of the US-China trade war, Chinese military acceleration, and its increasing surveillance sometimes extending up to the Indian Ocean. More recently, there have been reports that China has deployed its highly sophisticated surveillance ships in Andaman waters, clearly marking its intent in checking India’s naval preparedness and the advantage of the tri-services command in Andaman and Nicobar Islands. A similar situation is being confronted by Vietnam, an important partner in India’s Act East policy. It is time for countries to think of ways to adopt a collective strategy and not pursue a neutral and unilateral way, especially in SCS. ASEAN countries under the chairmanship of Vietnam in 2020 can be a platform for all littoral states to work together.

*** The author is an Economist and freelance writer on Indo-Vietnam Relations ***

![]()